History of the Haber process

[1][2] Well before the start of the industrial revolution, farmers would fertilize the land in various ways, mainly using feces and urine, well aware of the benefits of an intake of essential nutrients for plant growth.

[4] Scientists also already knew that nitrogen formed the dominant portion of the atmosphere, but manmade chemistry had yet to establish a means to fix it.

[9] During the interwar period, the lower cost of ammonia extraction from the virtually inexhaustible atmospheric reservoir contributed to the development of intensive agriculture and provided support for worldwide population growth.

Nitrogen fertilizers and synthetic products, such as urea and ammonium nitrate, are mainstays of industrial agriculture, and are essential to the nourishment of at least two billion people.

Half of the nitrogen in the great quantities of synthetic fertilizers employed today is not assimilated by plants but finds its way into rivers and the atmosphere as volatile chemical compounds.

Justus von Liebig (1803 – 1873), German chemist and founder of industrial agriculture, claimed that England had "stolen" 3.5 million skeletons from Europe to obtain phosphorus for fertilizer.

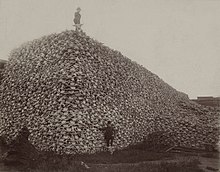

Throughout the nineteenth century, bison bones from the American West were brought back to East Coast factories for the production of phosphorus and phosphate fertilizer.

The guano-boom increased economic activity in Peru considerably for a few decades until all 12.5 million tons of guano deposits were exhausted.

"[19] In the late nineteenth century, chemists, including William Crookes, President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1898,[20][21] predicted that the demand for nitrogen compounds, either in the form of fertilizer or explosives, would exceed supply in the near future.

To ensure food security for Europe's growing population, it was essential that a new economical and reliable method of obtaining ammonia be developed.

[33] Wilhelm Ostwald, considered one of the best German chemists of the early twentieth century, attempted to synthesize ammonia in 1900 using an invention.

In 1905, German chemist Fritz Haber published Thermodynamik technischer Gasreaktionen (The Thermodynamics of Technical Gas Reactions), a book more concerned about the industrial application of chemistry than to its theoretical study.

[41][42] A few years later, Haber used results published by Nernst on the chemical equilibrium of ammonia and his own familiarity with high pressure chemistry and the liquefaction of air, to develop a new nitrogen fixation process.

[54] In March 1909, Haber demonstrated to his laboratory colleagues that he had finally found a process capable of fixing atmospheric dinitrogen sufficient to consider its industrialization.

[57] According to Bernthsen, no industrial device was capable of withstanding such high pressure and temperature for a long enough period to pay off the investment.

In addition, it appeared to him that the catalytic potential of osmium could disappear with use, which required its regular replacement despite the metal being scarce on Earth.

[58] However, Carl Engler, a chemist and university professor, wrote to BASF President Heinrich von Brunck to convince him to talk to Haber.

Von Brunck, along with Bernthsen and Carl Bosch, went to Haber's laboratory to determine whether BASF should engage in industrialization of the process.

[58] The latter had already worked in metallurgy, and his father had installed a mechanical workshop at home where the young Carl had learned to handle different tools.

In July 1909, BASF employees came to check on Haber's success again: the laboratory equipment fixed the nitrogen from the air, in the form of liquid ammonia, at a rate of about 250 milliliters every two hours.

[65] Carl Bosch, future head of industrialization of the process, reported that the key factor that prompted BASF to embark on this path was the improvement of the efficiency of the catalyst.