History of the battery

The introduction of nickel and lithium based batteries in the latter half of the 20th century made the development of innumerable portable electronic devices feasible, from powerful flashlights to mobile phones.

Very large stationary batteries find some applications in grid energy storage, helping to stabilize electric power distribution networks.

As an early form of capacitor, Leyden jars, unlike electrochemical cells, stored their charge physically and would release it all at once.

Many experimenters took to hooking several Leyden jars together to create a stronger charge and one of them, the colonial American inventor Benjamin Franklin, may have been the first to call his grouping an "electrical battery", a play on the military term for weapons functioning together.

[1][2] Based on some findings by Luigi Galvani, Alessandro Volta, a friend and fellow scientist, believed observed electrical phenomena were caused by two different metals joined by a moist intermediary.

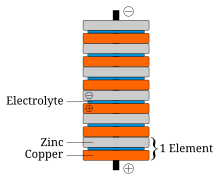

In 1800, Volta invented the first true battery, storing and releasing a charge through a chemical reaction instead of physically, which came to be known as the voltaic pile.

Volta's illustrations of his Crown of Cups and voltaic pile have extra metal disks, now known to be unnecessary, on both the top and bottom.

Volta's original pile models had some technical flaws, one of them involving the electrolyte leaking and causing short-circuits due to the weight of the discs compressing the brine-soaked cloth.

A Scotsman named William Cruickshank solved this problem by laying the elements in a box instead of piling them in a stack.

[4] Volta himself invented a variant that consisted of a chain of cups filled with a salt solution, linked together by metallic arcs dipped into the liquid.

The first was that the current produced electrolyzed the electrolyte solution, resulting in a film of hydrogen bubbles forming on the copper, which steadily increased the internal resistance of the battery (this effect, called polarization, is counteracted in modern cells by additional measures).

The latter problem was solved in 1835 by the English inventor William Sturgeon, who found that amalgamated zinc, whose surface had been treated with some mercury, did not suffer from local action.

The Daniell cell was a great improvement over the existing technology used in the early days of battery development and was the first practical source of electricity.

[7] A version of the Daniell cell was invented in 1837 by the Guy's Hospital physician Golding Bird who used a plaster of Paris barrier to keep the solutions separate.

The porous pot version of the Daniell cell was invented by John Dancer, a Liverpool instrument maker, in 1838.

The gravity cell consists of a glass jar, in which a copper cathode sits on the bottom and a zinc anode is suspended beneath the rim.

The German scientist Johann Christian Poggendorff overcame the problems with separating the electrolyte and the depolariser using a porous earthenware pot in 1842.

Although the chemistry is principally the same, the two acids are once again separated by a porous container and the zinc is treated with mercury to form an amalgam.

However, it can produce remarkably large currents in surges, because it has very low internal resistance, meaning that a single battery can be used to power multiple circuits.

In the early 1930s, a gel electrolyte (instead of a liquid) produced by adding silica to a charged cell was used in the LT battery of portable vacuum-tube radios.

In 1866, Georges Leclanché invented a battery that consists of a zinc anode and a manganese dioxide cathode wrapped in a porous material, dipped in a jar of ammonium chloride solution.

[15] The NCC improved Gassner's model by replacing the plaster of Paris with coiled cardboard, an innovation that left more space for the cathode and made the battery easier to assemble.

It was the first convenient battery for the masses and made portable electrical devices practical, and led directly to the invention of the flashlight.

[17][18] In 1893, Sakizō Yai's dry-battery was exhibited in World's Columbian Exposition and commanded considerable international attention.

Urry's battery consists of a manganese dioxide cathode and a powdered zinc anode with an alkaline electrolyte.

The low atomic weight and small size of its ions also speeds its diffusion, likely making it an ideal battery material.

In 1981, Japanese chemists Tokio Yamabe and Shizukuni Yata discovered a novel nano-carbonacious-PAS (polyacene)[31] and found that it was very effective for the anode in the conventional liquid electrolyte.

[34] In 2019, John Goodenough, Stanley Whittingham, and Akira Yoshino, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for their development of lithium-ion batteries.

These batteries hold their electrolyte in a solid polymer composite instead of in a liquid solvent, and the electrodes and separators are laminated to each other.

High costs and concerns about mineral extraction associated with lithium chemistry have renewed interest in sodium-ion battery development, with early electric vehicle product launches in 2023.