History of thermodynamics

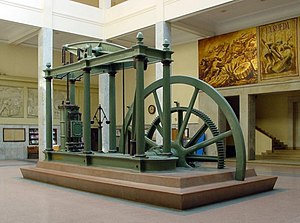

Due to the relevance of thermodynamics in much of science and technology, its history is finely woven with the developments of classical mechanics, quantum mechanics, magnetism, and chemical kinetics, to more distant applied fields such as meteorology, information theory, and biology (physiology), and to technological developments such as the steam engine, internal combustion engine, cryogenics and electricity generation.

The idea that heat is a form of motion is perhaps an ancient one and is certainly discussed by the English philosopher and scientist Francis Bacon in 1620 in his Novum Organum.

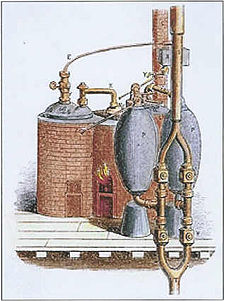

Denis Papin, an associate of Boyle's, built in 1679 a bone digester, which is a closed vessel with a tightly fitting lid that confines steam until a high pressure is generated.

This made it suitable for mechanical work in addition to pumping to heights beyond 30 feet, and is thus often considered the first true steam engine.

An early scientific reflection on the microscopic and kinetic nature of matter and heat is found in a work by Mikhail Lomonosov, in which he wrote: "Movement should not be denied based on the fact it is not seen.

Just as in this case motion ... remains hidden in warm bodies due to the extremely small sizes of the moving particles."

During the same years, Daniel Bernoulli published his book Hydrodynamics (1738), in which he derived an equation for the pressure of a gas considering the collisions of its atoms with the walls of a container.

Bodies were capable of holding a certain amount of this fluid, leading to the term heat capacity, named and first investigated by Scottish chemist Joseph Black in the 1750s.

Prior to 1698 and the invention of the Savery engine, horses were used to power pulleys, attached to buckets, which lifted water out of flooded salt mines in England.

Joseph Black and Antoine Lavoisier made important contributions in the precise measurement of heat changes using the calorimeter, a subject which became known as thermochemistry.

The development of the steam engine focused attention on calorimetry and the amount of heat produced from different types of coal.

The first substantial experimental challenges to the caloric theory arose in a work by Benjamin Thompson's (Count Rumford) from 1798, in which he showed that boring cast iron cannons produced great amounts of heat which he ascribed to friction.

As a result of his experiments in 1798, Thompson suggested that heat was a form of motion, though no attempt was made to reconcile theoretical and experimental approaches, and it is unlikely that he was thinking of the vis viva principle.

(The name "thermodynamics", however, did not arrive until 1854, when the British mathematician and physicist William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) coined the term thermo-dynamics in his paper On the Dynamical Theory of Heat.

Though it had come to be suspected from Scheele's work, in 1831 Macedonio Melloni demonstrated that radiant heat could be reflected, refracted and polarised in the same way as light.

John James Waterston in 1843 provided a largely accurate account, again independently, but his work received the same reception, failing peer review.

Further progress in kinetic theory started only in the middle of the 19th century, with the works of Rudolf Clausius, James Clerk Maxwell, and Ludwig Boltzmann.

Quantitative studies by Joule from 1843 onwards provided soundly reproducible phenomena, and helped to place the subject of thermodynamics on a solid footing.

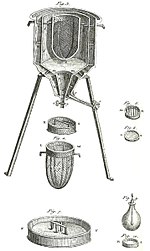

In 1845, Joule reported his best-known experiment, involving the use of a falling weight to spin a paddle-wheel in a barrel of water, which allowed him to estimate a mechanical equivalent of heat of 819 ft·lbf/Btu (4.41 J/cal).

In March 1851, while grappling to come to terms with the work of Joule, Lord Kelvin started to speculate that there was an inevitable loss of useful heat in all processes.

The idea was framed even more dramatically by Hermann von Helmholtz in 1854, giving birth to the spectre of the heat death of the universe.

Clausius' above statement interested the Scottish mathematician and physicist James Clerk Maxwell, who in 1859 derived the momentum distribution later named after him.

By introducing the concept of thermodynamic probability as the number of microstates corresponding to the current macrostate, he showed that its logarithm is proportional to entropy.

James Clerk Maxwell's 1862 insight that both light and radiant heat were forms of electromagnetic wave led to the start of the quantitative analysis of thermal radiation.

In 1879, Jožef Stefan observed that the total radiant flux from a blackbody is proportional to the fourth power of its temperature and stated the Stefan–Boltzmann law.

Building on the foundations above, Lars Onsager, Erwin Schrödinger, Ilya Prigogine and others, brought these engine "concepts" into the thoroughfare of almost every modern-day branch of science.