Hurricane Epsilon (2020)

[2] Afterward, Epsilon began to weaken as the system turned northward, with the storm dropping to Category 1 intensity late that day.

Hurricane Epsilon had non-tropical origins, developing from an upper-level trough associated with a weak baroclinic low that emerged off the East Coast of the United States on October 13.

[4] Around this time, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) first noted the possibility of a broad non-tropical low-pressure system forming within the trough several days later, identifying a chance that the disturbance could gradually organize and undergo tropical cyclogenesis.

On October 16, convective activity (or thunderstorms) began to increase and become better organized, as the cut-off low interacted with the degrading parent trough.

At 06:00 UTC on October 19, a large burst of deep convection developed just east of the surface low, causing the center to become more sufficiently organized, prompting the NHC to upgrade the disturbance into Tropical Depression Twenty-Seven.

[11][12] Early on October 20, water vapor imagery showed Epsilon interacting with a dissipating cold front to its north and a negatively-titled (oriented northwest to southeast) upper-level trough from the south.

[13] The system began to move northward and then northwestward, making a loop over the Central Atlantic, due to its smaller circulation interacting with its upper-level cyclonic flow.

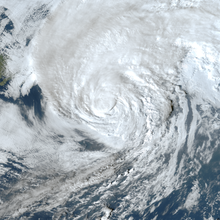

Even while battling weak-to-moderate deep-layer wind shear and some mid-level dry air, an eye-like feature started to become evident on visible and microwave imagery, giving Epsilon a more tropical structure, compared to its earlier hybrid appearance.

[4] At 03:00 UTC the next day, the NHC upgraded the strengthening tropical storm to a Category 1 hurricane, while it was located roughly 545 miles (877 km) east-southeast of Bermuda.

[16] However, the eastern and southern sides of the eyewall were rather thin, even as Epsilon shifted west-northwestward, due to a mid-tropospheric ridge located north of the cyclone.

[17] Despite this, just a few hours later, microwave imagery showed a closed eyewall with deep convection enclosing the center, with a 15 miles (24 km) eye visible.

[2] At 00:00 UTC on October 22, Epsilon reached its peak intensity, with 1-minute sustained winds of around 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of around 952 mbar (28.11 inHg).

[4] Shortly afterward, Epsilon began to degrade due to a dry air intrusion, and its eye started to become ill-defined and cloud-filled, while its western eyewall eroded, causing the storm to weaken to a Category 2 hurricane.

[25] At 15:00 UTC on October 23, a small eye reappeared on geostationary and polar-orbiting microwave imagery, along with increased well-defined curved banding.

[32][4] At 06:00 UTC on October 26, Epsilon finished transitioning into an extratropical cyclone while located about 565 miles (909 km) east of Cape Race, Newfoundland, with the storm's low-level circulation becoming stretched out along a north–south axis.

[4] Epsilon's large wind field prompted the issuance of a tropical storm watch for Bermuda at 15:00 UTC on October 20,[34] which was later upgraded to a warning 24 hours later.

[41][4] The outer bands of the storm only brought scattered showers to Bermuda, with a peak precipitation amount of 0.42 inches (11 mm) being reported at the L.F. Wade International Airport.

[4] Epsilon produced dangerous swells along the coast of Bermuda, forcing lifeguards at Horseshoe Bay to briefly halt services.

[37][43][44] Epsilon produced large swells and rip currents from the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico, northward through the entire East Coast of the United States.

[45] On the island of Puerto Rico, coastal flood and rip current advisories were issued by the National Weather Service (NWS) office in San Juan.

[48] Increased swells and rip currents also threatened swimmers in South Carolina, causing red flags to be raised in Myrtle Beach.

[54] Yellow rain warnings were also issued for parts of North West England, with the storm causing disruptions to train and bus services, and threatening flooding.

[56] In Northern Ireland, large swells of up to 98 feet (30 m) in height were recorded by offshore buoys, sending skilled surfers to beaches, as spectators watched waves crash onshore.

Meanwhile, the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) warned residents of "colossal swells" and "extremely dangerous conditions", advising people to avoid swimming in the ocean.

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown