Japonisme

Japonisme[a] is a French term that refers to the popularity and influence of Japanese art and design among a number of Western European artists in the nineteenth century following the forced reopening of foreign trade with Japan in 1858.

[8] From a long history of making weapons for samurai, Japanese metalworkers had achieved an expressive range of colours by combining and finishing metal alloys.

[11] These items were widely visible in nineteenth-century Europe: a succession of world's fairs displayed Japanese decorative art to millions,[12][13] and it was picked up by galleries and fashionable stores.

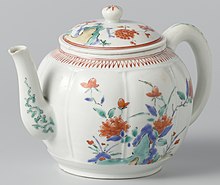

[20] The production of Japanese porcelain increased in the seventeenth century, after Korean potters were brought to the Kyushu area.

[21] The immigrants, their descendants, and Japanese counterparts unearthed kaolin clay mines and began to make high quality pottery.

Marie Antoinette and Maria Theresa are known collectors of Japanese lacquerware, and their collections are often exhibited in the Louvre and the Palace of Versailles.

[24] During the Kaei era (1848–1854), after more than 200 years of seclusion, foreign merchant ships of various nationalities began to visit Japan.

Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan ended a long period of national isolation and became open to imports from the West, including photography and printing techniques.

With this new opening in trade, Japanese art and artifacts began to appear in small curiosity shops in Paris and London.

[27] Around 1856, the French artist Félix Bracquemond encountered a copy of the sketch book Hokusai Manga at the workshop of his printer, Auguste Delâtre.

[28] La Porte Chinoise, in particular, attracted artists James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Édouard Manet, and Edgar Degas who drew inspiration from the prints.

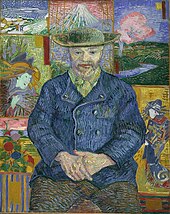

[31] Van Gogh used Régamey as a reliable source for the artistic practices and everyday scenes of Japanese life.

Inspired by Japanese woodblock prints and their colorful palettes, Van Gogh incorporated a similar vibrancy into his own works.

[27] The estimated date of Degas' adoption of japonismes into his prints is 1875, and it can be seen in his choice to divide individual scenes by placing barriers vertically, diagonally, and horizontally.

[39] The atypical positioning of his female figures and the dedication to reality in his prints aligned him with Japanese printmakers such as Hokusai, Utamaro, and Sukenobu.

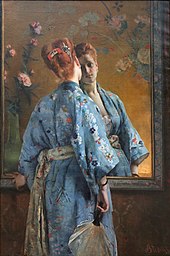

[45] Rather than copying specific artists and artworks, Whistler was influenced by general Japanese methods of articulation and composition, which he integrated into his works.

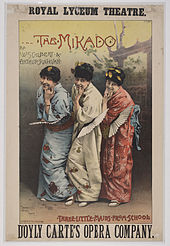

This comic opera enjoyed immense popularity throughout Europe where seventeen companies performed it 9,000 times within two years of its premiere.

They were not without lasting effect, however, and the geisha had established herself among the scrolls, jade, and images of Mount Fuji that signified Japan to the West.

Just as ukiyo-e had proven useful in France, severed from any understanding of Japan, the troupes of Japanese actors and dancers that toured Europe provided materials for "a new way of dramatizing" on stage.

Karl Lautenschlager adopted the Kabuki revolving stage in 1896 and ten years later Max Reinhardt employed it in the premiere of Frühlings Erwachen by Frank Wedekind.

[48] Conder's principles have sometimes proved hard to follow:[citation needed] Robbed of its local garb and mannerisms, the Japanese method reveals aesthetic principles applicable to the gardens of any country, teaching, as it does, how to convert into a poem or picture a composition, which, with all its variety of detail, otherwise lacks unity and intent.

[49]Tassa (Saburo) Eida created several influential gardens, two for the Japan–British Exhibition in London in 1910 and one built over four years for William Walker, 1st Baron Wavertree.

The impressionist painter Claude Monet modelled parts of his garden in Giverny after Japanese elements, such as the bridge over the lily pond, which he painted numerous times.

In this series, by detailing just on a few select points such as the bridge or the lilies, he was influenced by traditional Japanese visual methods found in ukiyo-e prints, of which he had a large collection.

In the United States, the fascination with Japanese art extended to collectors and museums creating significant collections which still exist and have influenced many generations of artists.