Medieval art

[2] Apart from the formal aspects of classicism, there was a continuous tradition of realistic depiction of objects that survived in Byzantine art throughout the period, while in the West it appears intermittently, combining and sometimes competing with new expressionist possibilities developed in Western Europe and the Northern legacy of energetic decorative elements.

At the start of the medieval period most significant works of art were very rare and costly objects associated with secular elites, monasteries or major churches and, if religious, largely produced by monks.

The Middle Ages generally lacked the concept of preserving older works for their artistic merit, as opposed to their association with a saint or founder figure, and the following periods of the Renaissance and Baroque tended to disparage medieval art.

Many objects using precious metals were made in the knowledge that their bullion value might be realised at a future point—only near the end of the period could money be invested other than in real estate, except at great risk or by committing usury.

The even more expensive pigment ultramarine, made from ground lapis lazuli obtainable only from Afghanistan, was used lavishly in the Gothic period, more often for the traditional blue outer mantle of the Virgin Mary than for skies.

As thin ivory panels carved in relief could rarely be recycled for another work, the number of survivals is relatively high—the same is true of manuscript pages, although these were often re-cycled by scraping, whereupon they become palimpsests.

[8] Paper became available in the last centuries of the period, but was also extremely expensive by today's standards; woodcuts sold to ordinary pilgrims at shrines were often matchbook size or smaller.

Modern dendrochronology has revealed that most of the oak for panels used in Early Netherlandish painting of the 15th century was felled in the Vistula basin in Poland, from where it was shipped down the river and across the Baltic and North Seas to Flemish ports, before being seasoned for several years.

From the start of the period the main survivals of Christian art are the tomb-paintings in popular styles of the catacombs of Rome, but by the end there were a number of lavish mosaics in churches built under Imperial patronage.

Byzantine art was extremely conservative, for religious and cultural reasons, but retained a continuous tradition of Greek realism, which contended with a strong anti-realist and hieratic impulse.

For example, Byzantine silk textiles, often woven or embroidered with designs of both animal and human figures, the former often reflecting traditions originating much further east, were unexcelled in the Christian world until almost the end of the Empire.

Most artworks were small and portable and those surviving are mostly jewellery and metalwork, with the art expressed in geometric or schematic designs, often beautifully conceived and made, with few human figures and no attempt at realism.

Viking art from later centuries in Scandinavia and parts of the British Isles includes work from both pagan and Christian backgrounds, and was one of the last flowerings of this broad group of styles.

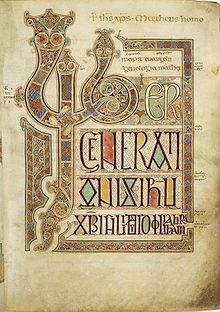

"Franco-Saxon" is a term for a school of late Carolingian illumination in north-eastern France that used insular-style decoration, including super-large initials, sometimes in combination with figurative images typical of contemporary French styles.

[18] Giant initials Islamic art during the Middle Ages falls outside the scope of this article, but it was widely imported and admired by European elites, and its influence needs mention.

Glass production, for example, remained a Jewish speciality throughout the period, and Christian art, as in Coptic Egypt continued, especially during the earlier centuries, keeping some contacts with Europe.

The Mozarabic art of Christian Spain had strong Islamic influence, and a complete lack of interest in realism in its brilliantly coloured miniatures, where figures are presented as entirely flat patterns.

Figurative sculpture, originally colourfully painted, plays an integral and important part in these buildings, in the capitals of columns, as well as around impressive portals, usually centred on a tympanum above the main doors, as at Vézelay Abbey and Autun Cathedral.

Large carvings also became important, especially painted wooden crucifixes like the Gero Cross from the very start of the period, and figures of the Virgin Mary like the Golden Madonna of Essen.

At the same time grotesque beasts and monsters, and fights with or between them, were popular themes, to which religious meanings might be loosely attached, although this did not impress St Bernard of Clairvaux, who famously denounced such distractions in monasteries: But in the cloister, in the sight of the reading monks, what is the point of such ridiculous monstrosity, the strange kind of shapely shapelessness?

The majority of Romanesque cathedrals and large churches were replaced by Gothic buildings, at least in those places benefiting from the economic growth of the period—Romanesque architecture is now best seen in areas that were subsequently relatively depressed, like many southern regions of France and Italy, or northern Spain.

Secular buildings also often had wall-paintings, although royalty preferred the much more expensive tapestries, which were carried along as they travelled between their many palaces and castles, or taken with them on military campaigns—the finest collection of late-medieval textile art comes from the Swiss booty at the Battle of Nancy, when they defeated and killed Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, and captured all his baggage train.

The process of establishing a distinct Western style was begun by Cimabue and Duccio, and completed by Giotto, who is traditionally regarded as the starting point for the development of Renaissance painting.

In the mid-15th century Burgundian miniature (right) the artist seems keen to show his skill at representing buildings and blocks of stone obliquely, and managing scenes at different distances.

Sections of the composition are at a similar scale, with relative distance shown by overlapping, foreshortening, and further objects being higher than nearer ones, though the workmen at left do show finer adjustment of size.

These were images of moments detached from the narrative of the Passion of Christ designed for meditation on his sufferings, or those of the Virgin: the Man of Sorrows, Pietà, Veil of Veronica or Arma Christi.

In the cheap blockbooks with text (often in the vernacular) and images cut in a single woodcut, works such as that illustrated (left), the Ars Moriendi (Art of Dying) and typological verse summaries of the bible like the Speculum Humanae Salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation) were the most popular.

Renaissance Humanism and the rise of a wealthy urban middle class, led by merchants, began to transform the old social context of art, with the revival of realistic portraiture and the appearance of printmaking and the self-portrait, together with the decline of forms like stained glass and the illuminated manuscript.

Donor portraits, in the Early Medieval period largely the preserve of popes, kings and abbots, now showed businessmen and their families, and churches were becoming crowded with the tomb monuments of the well-off.

Secular works, often using subjects concerned with courtly love or knightly heroism, were produced as illuminated manuscripts, carved ivory mirror-cases, tapestries and elaborate gold table centrepieces like nefs.