Protein

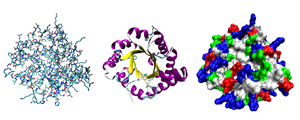

Like other biological macromolecules such as polysaccharides and nucleic acids, proteins are essential parts of organisms and participate in virtually every process within cells.

Osborne, alongside Lafayette Mendel, established several nutritionally essential amino acids in feeding experiments with laboratory rats.

In the 1950s, the Armour Hot Dog Company purified 1 kg of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A and made it freely available to scientists.

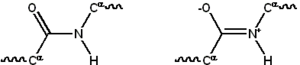

[15] Linus Pauling is credited with the successful prediction of regular protein secondary structures based on hydrogen bonding, an idea first put forth by William Astbury in 1933.

[16] Later work by Walter Kauzmann on denaturation,[17][18] based partly on previous studies by Kaj Linderstrøm-Lang,[19] contributed an understanding of protein folding and structure mediated by hydrophobic interactions.

[45] The most abundant protein in nature is thought to be RuBisCO, an enzyme that catalyzes the incorporation of carbon dioxide into organic matter in photosynthesis.

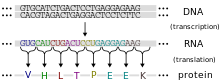

In contrast, eukaryotes make mRNA in the cell nucleus and then translocate it across the nuclear membrane into the cytoplasm, where protein synthesis then takes place.

[39] The largest known proteins are the titins, a component of the muscle sarcomere, with a molecular mass of almost 3,000 kDa and a total length of almost 27,000 amino acids.

Chemical synthesis is inefficient for polypeptides longer than about 300 amino acids, and the synthesized proteins may not readily assume their native tertiary structure.

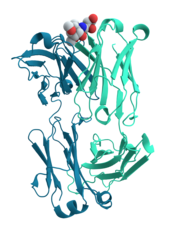

Such changes are often induced by the binding of a substrate molecule to an enzyme's active site, or the physical region of the protein that participates in chemical catalysis.

[42]: 165–85 A special case of intramolecular hydrogen bonds within proteins, poorly shielded from water attack and hence promoting their own dehydration, are called dehydrons.

Protein–protein interactions regulate enzymatic activity, control progression through the cell cycle, and allow the assembly of large protein complexes that carry out many closely related reactions with a common biological function.

The ability of binding partners to induce conformational changes in proteins allows the construction of enormously complex signaling networks.

Others are membrane proteins that act as receptors whose main function is to bind a signaling molecule and induce a biochemical response in the cell.

[41]: 251–81 Antibodies are protein components of an adaptive immune system whose main function is to bind antigens, or foreign substances in the body, and target them for destruction.

The canonical example of a ligand-binding protein is haemoglobin, which transports oxygen from the lungs to other organs and tissues in all vertebrates and has close homologs in every biological kingdom.

[54]: 481, 490 Methods commonly used to study protein structure and function include immunohistochemistry, site-directed mutagenesis, X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectrometry.

[70] Proteins may be purified from other cellular components using a variety of techniques such as ultracentrifugation, precipitation, electrophoresis, and chromatography;[36]: 21–24 the advent of genetic engineering has made possible a number of methods to facilitate purification.

To simplify this process, genetic engineering is often used to add chemical features to proteins that make them easier to purify without affecting their structure or activity.

Here, a "tag" consisting of a specific amino acid sequence, often a series of histidine residues (a "His-tag"), is attached to one terminus of the protein.

[74] Other methods for elucidating the cellular location of proteins requires the use of known compartmental markers for regions such as the ER, the Golgi, lysosomes or vacuoles, mitochondria, chloroplasts, plasma membrane, etc.

For example, immunohistochemistry usually uses an antibody to one or more proteins of interest that are conjugated to enzymes yielding either luminescent or chromogenic signals that can be compared between samples, allowing for localization information.

The sample is prepared for normal electron microscopic examination, and then treated with an antibody to the protein of interest that is conjugated to an extremely electro-dense material, usually gold.

[78] Through another genetic engineering application known as site-directed mutagenesis, researchers can alter the protein sequence and hence its structure, cellular localization, and susceptibility to regulation.

Common experimental methods include X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy, both of which can produce structural information at atomic resolution.

Examples include the multi-layer multi-configuration time-dependent Hartree method and the hierarchical equations of motion approach, which have been applied to plant cryptochromes[99] and bacteria light-harvesting complexes,[100] respectively.

[110] For instance, the ability of muscle tissue to continually expand and contract is directly tied to the elastic properties of their underlying protein makeup.

Outside of their biological context, the unique mechanical properties of many proteins, along with their relative sustainability when compared to synthetic polymers, have made them desirable targets for next-generation materials design.

[117][118] In comparison to this, globular proteins, such as Bovine Serum Albumin, which float relatively freely in the cytosol and often function as enzymes (and thus undergoing frequent conformational changes) have comparably much lower Young's moduli.

Using either atomistic force-fields, such as CHARMM or GROMOS, or coarse-grained forcefields like Martini,[121] a single protein molecule can be stretched by a uniaxial force while the resulting extension is recorded in order to calculate the strain.