Damping

[1][2] Damping is an influence within or upon an oscillatory system that has the effect of reducing or preventing its oscillation.

[3] Examples of damping include viscous damping in a fluid (see viscous drag), surface friction, radiation,[1] resistance in electronic oscillators, and absorption and scattering of light in optical oscillators.

Damping is not to be confused with friction, which is a type of dissipative force acting on a system.

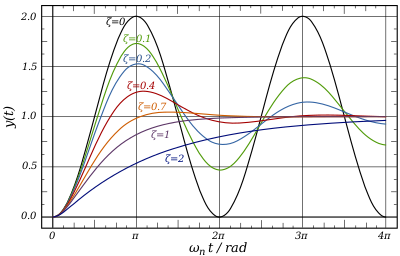

The damping ratio is a dimensionless measure describing how oscillations in a system decay after a disturbance.

Many systems exhibit oscillatory behavior when they are disturbed from their position of static equilibrium.

Sometimes losses (e.g. frictional) damp the system and can cause the oscillations to gradually decay in amplitude towards zero or attenuate.

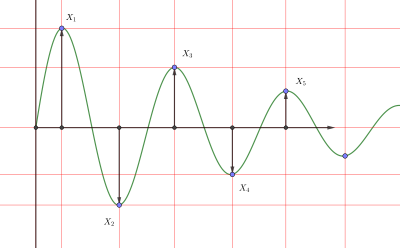

The damping ratio is a measure describing how rapidly the oscillations decay from one bounce to the next.

The physical quantity that is oscillating varies greatly, and could be the swaying of a tall building in the wind, or the speed of an electric motor, but a normalised, or non-dimensionalised approach can be convenient in describing common aspects of behavior.

Depending on the amount of damping present, a system exhibits different oscillatory behaviors and speeds.

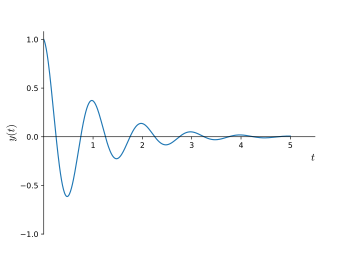

[6] Damped sine waves are commonly seen in science and engineering, wherever a harmonic oscillator is losing energy faster than it is being supplied.

That is, when you connect the maximum point of each successive curve, the result resembles an exponential decay function.

and the definition of the damping ratio above, we can rewrite this as: This equation is more general than just the mass–spring system, and also applies to electrical circuits and to other domains.

It can be solved with the approach where C and s are both complex constants, with s satisfying Two such solutions, for the two values of s satisfying the equation, can be combined to make the general real solutions, with oscillatory and decaying properties in several regimes: The Q factor, damping ratio ζ, and exponential decay rate α are related such that[9] When a second-order system has

[10] For example, a high quality tuning fork, which has a very low damping ratio, has an oscillation that lasts a long time, decaying very slowly after being struck by a hammer.

In control theory, overshoot refers to an output exceeding its final, steady-state value.

The percentage overshoot (PO) is related to damping ratio (ζ) by: Conversely, the damping ratio (ζ) that yields a given percentage overshoot is given by: When an object is falling through the air, the only force opposing its freefall is air resistance.

[14] Electrical systems that operate with alternating current (AC) use resistors to damp LC resonant circuits.

[14] Kinetic energy that causes oscillations is dissipated as heat by electric eddy currents which are induced by passing through a magnet's poles, either by a coil or aluminum plate.

Eddy currents are a key component of electromagnetic induction where they set up a magnetic flux directly opposing the oscillating movement, creating a resistive force.