Gene expression

The process of gene expression is used by all known life—eukaryotes (including multicellular organisms), prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea), and utilized by viruses—to generate the macromolecular machinery for life.

Such phenotypes are often displayed by the synthesis of proteins that control the organism's structure and development, or that act as enzymes catalyzing specific metabolic pathways.

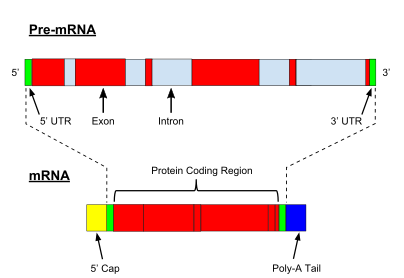

All steps in the gene expression process may be modulated (regulated), including the transcription, RNA splicing, translation, and post-translational modification of a protein.

Because these transcripts can be potentially translated into different proteins, splicing extends the complexity of eukaryotic gene expression and the size of a species proteome.

The pre-rRNA is cleaved and modified (2′-O-methylation and pseudouridine formation) at specific sites by approximately 150 different small nucleolus-restricted RNA species, called snoRNAs.

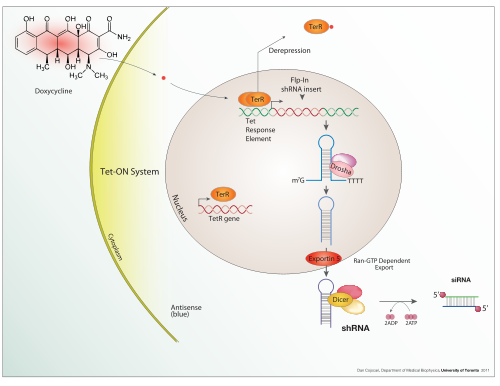

After being exported, it is then processed to mature miRNAs in the cytoplasm by interaction with the endonuclease Dicer, which also initiates the formation of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), composed of the Argonaute protein.

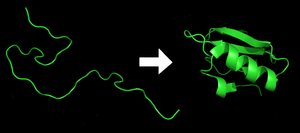

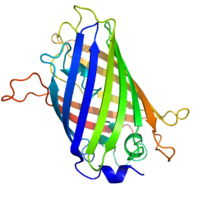

[29] Each protein exists as an unfolded polypeptide or random coil when translated from a sequence of mRNA into a linear chain of amino acids.

[30] Amino acids interact with each other to produce a well-defined three-dimensional structure, the folded protein (the right hand side of the figure) known as the native state.

More generally, gene regulation gives the cell control over all structure and function, and is the basis for cellular differentiation, morphogenesis and the versatility and adaptability of any organism.

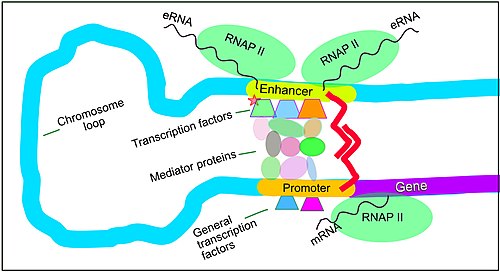

In general gene expression is regulated through changes[46] in the number and type of interactions between molecules[47] that collectively influence transcription of DNA[48] and translation of RNA.

[55] The activity of transcription factors is further modulated by intracellular signals causing protein post-translational modification including phosphorylation, acetylation, or glycosylation.

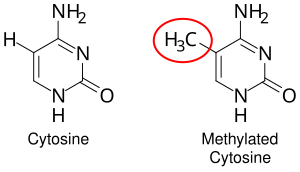

[64] In eukaryotes the structure of chromatin, controlled by the histone code, regulates access to DNA with significant impacts on the expression of genes in euchromatin and heterochromatin areas.

[72] Enhancers, when active, are generally transcribed from both strands of DNA with RNA polymerases acting in two different directions, producing two eRNAs as illustrated in the figure.

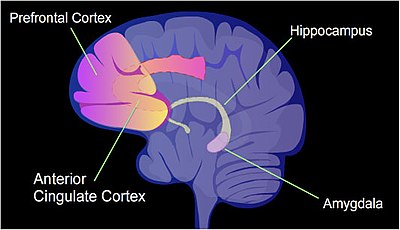

The pattern of induced and repressed genes within neurons appears to provide a molecular basis for forming the first transient memory of this training event in the hippocampus of the rat brain.

[95] By binding to specific sites within the 3′-UTR, miRNAs can decrease gene expression of various mRNAs by either inhibiting translation or directly causing degradation of the transcript.

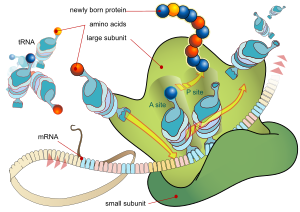

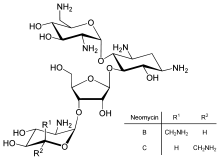

[108] Inhibition of protein translation is a major target for toxins and antibiotics, so they can kill a cell by overriding its normal gene expression control.

[111] Proteolysis, other than being involved in breaking down proteins, is also important in activating and deactivating them, and in regulating biological processes such as DNA transcription and cell death.

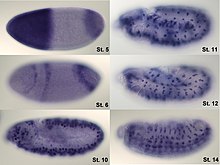

[118] Because the use of radioactive reagents makes the procedure time-consuming and potentially dangerous, alternative labeling and detection methods, such as digoxigenin and biotin chemistries, have been developed.

[119] Perceived disadvantages of Northern blotting are that large quantities of RNA are required and that quantification may not be completely accurate, as it involves measuring band strength in an image of a gel.

The cDNA template is then amplified in the quantitative step, during which the fluorescence emitted by labeled hybridization probes or intercalating dyes changes as the DNA amplification process progresses.

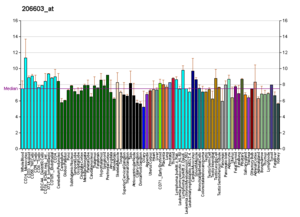

[127] Alternatively, "tag based" technologies like Serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) and RNA-Seq, which can provide a relative measure of the cellular concentration of different mRNAs, can be used.

Although NGS is comparatively time-consuming, expensive, and resource-intensive, it can identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms, splice-variants, and novel genes, and can also be used to profile expression in organisms for which little or no sequence information is available.

For genes encoding proteins, the expression level can be directly assessed by a number of methods with some clear analogies to the techniques for mRNA quantification.

The gel-based nature of this assay makes quantification less accurate, but it has the advantage of being able to identify later modifications to the protein, for example proteolysis or ubiquitination, from changes in size.

By replacing the gene with a new version fused to a green fluorescent protein marker or similar, expression may be directly quantified in live cells.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay works by using antibodies immobilised on a microtiter plate to capture proteins of interest from samples added to the well.

Doxycycline is also used in "Tet-on" and "Tet-off" tetracycline controlled transcriptional activation to regulate transgene expression in organisms and cell cultures.

In addition to these biological tools, certain naturally observed configurations of DNA (genes, promoters, enhancers, repressors) and the associated machinery itself are referred to as an expression system.

There are several ways to construct gene expression networks, but one common approach is to compute a matrix of all pair-wise correlations of expression across conditions, time points, or individuals and convert the matrix (after thresholding at some cut-off value) into a graphical representation in which nodes represent genes, transcripts, or proteins and edges connecting these nodes represent the strength of association (see GeneNetwork GeneNetwork 2).

[136] The following experimental techniques are used to measure gene expression and are listed in roughly chronological order, starting with the older, more established technologies.