History of manufactured fuel gases

Coal gas also contains significant quantities of unwanted sulfur and ammonia compounds, as well as heavy hydrocarbons, and must be purified before use.

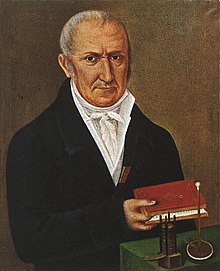

The first attempts to manufacture fuel gas in a commercial way were made in the period 1795–1805 in France by Philippe LeBon, and in England by William Murdoch.

After Joseph Black realized that carbon dioxide was in fact a different sort of gas altogether from atmospheric air, other gases were identified, including hydrogen by Henry Cavendish in 1766.

A professor of natural philosophy at the University of Louvain Jan Pieter Minckeleers and two of his colleagues were asked by their patron, the Duke of Arenberg, to investigate ballooning.

His goal was to raise sufficient funds from investors to launch a company, but he failed to attract this sort of interest, either from the French state or from private sources.

Although he was given a forest concession by the French government to experiment with the manufacture of tar from wood for naval use, he never succeed with the thermolamp, and died in uncertain circumstances in 1805.

There were also thermolamps designed and built in Germany, the most important of which were by Zachaus Winzler, an Austrian chemist who ran a saltpetre factory in Blansko.

[5][6] William Murdoch (sometimes Murdock) (1754–1839) was an engineer working for the firm of Boulton & Watt, when, while investigating distillation processes sometime in 1792–1794, he began using coal gas for illumination.

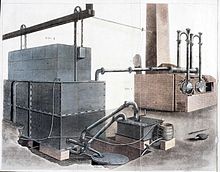

[7][8] After an initial installation at the Soho Foundry in 1803–1804, Boulton & Watt prepared an apparatus for the textile firm of Philips & Lee in Salford near Manchester in 1805–1806.

In that year, the committee made a serious attempt to get the House of Commons to pass a bill empowering the king to grant the charter, but Boulton & Watt felt their gaslight apparatus manufacturing business was threatened and mounted an opposition through their allies in Parliament.

The government was also interested in promoting the industry, and in 1817 commissioned Chabrol de Volvic to study the technology and build a prototype plant, also in Paris.

[23] However, as time went by, gas-works began to be seen as more as a double-edged sword – and eventually as a positive good, as former nuisances were abated by technological improvements, and the full benefits of gas became clear.

Upon being shut down, few former manufactured gas plant sites were brought to an acceptable level of environmental cleanliness to allow for their re-use, at least by contemporary standards.

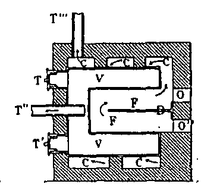

Over the years of manufactured gas production, advances were made that turned the retort-bench from little more than coal-containing iron vessels over an open fire to a massive, highly efficient, partially automated, industrial-scale, capital-intensive plant for the carbonization of large amounts of coal.

Initially, retort benches were of many different configurations due to the lack of long use and scientific and practical understanding of the carbonization of coal.

As higher heats became possible, advanced methods of retort bench firing were introduced, catalyzed by the development of the open hearth furnace by Siemens, circa 1855–1870, leading to a revolution in gas-works efficiency.

Each retort ascension pipe dropped under the water level by at least a small amount, perhaps by an inch, but often considerably more in the earlier days of gas manufacture.

The major difference between the multitubular and water-tube condenser was that in the former the water passed outside and around the tubes which carry the hot gas, and in the latter type, the opposite was the case.

[26] As extremely finely divided particles were also suspended in the gas, it was impossible to separate the particulate matter solely by a reduction of vapor pressure.

This prototype machine was followed by others of improved construction; notably by Kirkham, Hulett, and Chandler, who introduced the well-known Standard Washer Scrubber, Holmes, of Huddersfield, and others.

Originally, purifiers were simple tanks of lime-water, also known as cream or milk of lime,[28] where the raw gas from the retort bench was bubbled through to remove the sulfuret of hydrogen.

Some enterprising gas entrepreneurs tried to sell it as a weed-killer, but most people wanted nothing to do with it, and generally, it was regarded as waste which was both smelly and poisonous, and gas-works could do little with, except bury.

Slaked lime (calcium hydroxide) was placed in thick layers on trays which were then inserted into a square or cylinder-shaped purifier tower which gas was then passed through, from the bottom to the top.

The outrageous stinks from many gas-works led many citizens to regard them as public nuisances, and attracted the eye of regulators, neighbors, and courts.

Enterprising gas-works engineers discovered that bog iron ore could be used to remove the sulfuretted hydrogen from the gas, and not only could it be used for such, but it could be used in the purifier, exposed to the air, whence it would be rejuvenated, without emitting noxious sulfuretted hydrogen gas, the sulfur being retained in the iron ore. Then it could be reinserted into the purifier, and reused and rejuvenated multiple times, until it was thoroughly embedded with sulfur.

In order to maintain a true vertical position, the vessel has rollers which work on guide-rails attached to the tank sides and to the columns surrounding the holder.

Steam was in use in many areas of the gasworks, including: For the operation of the exhauster; For scouring of pyrolysis char and slag from the retorts and for clinkering the producer of the bench; For the operation of engines used for conveying, compressing air, charging hydraulics, or the driving of dynamos or generators producing electric current; To be injected under the grate of the producer in the indirectly fired bench, so as to prevent the formation of clinker, and to aid in the water-gas shift reaction, ensuring high-quality secondary combustion; As a reactant in the (carburetted) water gas plant, as well as driving the equipment thereof, such as the numerous blowers used in that process, as well as the oil spray for the carburettor; For the operation of fire, water, liquid, liquor, and tar pumps; For the operation of engines driving coal and coke conveyor-belts; For clearing of chemical obstructions in pipes, including naphthalene & tar as well as general cleaning of equipment; For heating cold buildings in the works, for maintaining the temperature of process piping, and preventing freezing of the water of the gasholder, or congealment of various chemical tanks and wells.

As the gas industry applied scientific and rational design principles to its equipment, the importance of thermal management and capture from processes became common.

But storage in air-entrained confined spaces was not highly looked upon either, as residual heat removal would be difficult, and fighting a fire if it was started could result in the formation of highly toxic carbon monoxide through the water-gas reaction, caused by allowing water to pass over extremely hot carbon (H2O + C = H2 + CO), which would be dangerous outside, but deadly in a confined space.

Other variables included national security; for instance, the gasworks of Tegel in Berlin had some 1 million tons of coal (6 months of supply) in gigantic underwater bunker facilities half a mile long (Meade 2e, p. 379).