Prussian blue

The pigment is used in paints, it became prominent in 19th-century aizuri-e (藍摺り絵) Japanese woodblock prints, and it is the traditional "blue" in technical blueprints.

In medicine, orally administered Prussian blue is used as an antidote for certain kinds of heavy metal poisoning, e.g., by thallium(I) and radioactive isotopes of caesium.

The therapy exploits Prussian blue's ion-exchange properties and high affinity for certain "soft" metal cations.

European painters had previously used a number of pigments such as indigo dye, smalt, and Tyrian purple, and the extremely expensive ultramarine made from lapis lazuli.

[8][9][10] The pigment readily replaced the expensive lapis lazuli-derived ultramarine and was an important topic in the letters exchanged between Johann Leonhard Frisch and the president of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, between 1708 and 1716.

Frisch himself is the author of the first known publication of Prussian blue in the paper Notitia Coerulei Berolinensis nuper inventi in 1710, as can be deduced from his letters.

At around the same time, Prussian blue arrived in Paris, where Antoine Watteau and later his successors Nicolas Lancret and Jean-Baptiste Pater used it in their paintings.

Diesbach was attempting to create a red lake pigment from cochineal, but obtained the blue instead as a result of the contaminated potash he was using.

[14][15][16] In 1752, French chemist Pierre J. Macquer made the important step of showing Prussian blue could be reduced to a salt of iron and a new acid, which could be used to reconstitute the dye.

In the late 1800s, Rabbi Gershon Henoch Leiner, the Hasidic Rebbe of Radzin, dyed tzitziyot with Prussian blue made with sepia, believing that this was the true techeiles dye.

[21] As Dunkelblau (dark blue), this shade achieved a symbolic importance and continued to be worn by most German soldiers for ceremonial and off-duty occasions until the outbreak of World War I, when it was superseded by greenish-gray field gray (Feldgrau).

Oxidation of this white solid with hydrogen peroxide or sodium chlorate produces ferricyanide and affords Prussian blue.

[26] In former times, the addition of iron(II) salts to a solution of ferricyanide was thought to afford a material different from Prussian blue.

[30] The insertion of Na+ and K+ cations in the framework of potassium Prussian white provides favorable synergistic effects improving the long-term battery stability and increasing the number of possible recharge cycles, lengthening its service life.

[30] The large-size framework of Prussian white easily accommodating Na+ and K+ cations facilitates their intercalation and subsequent extraction during the charge/discharge cycles.

The spacious and rigid host crystal structure contributes to its volumetric stability against the internal swelling stress and strain developing in sodium-batteries after many cycles.

Neutron diffraction can easily distinguish N and C atoms, and it has been used to determine the detailed structure of Prussian blue and its analogs.

One-fourth of the sites of Fe(CN)6 subunits (supposedly at random) are vacant (empty), leaving three such groups on average per unit cell.

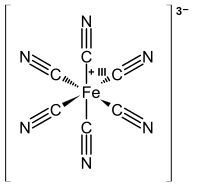

It is worth noting that in soluble hexacyanoferrates Fe(II or III) is always coordinated to the carbon atom of a cyanide, whereas in crystalline Prussian blue Fe ions are coordinated to both C and N.[43] The composition is notoriously variable due to the presence of lattice defects, allowing it to be hydrated to various degrees as water molecules are incorporated into the structure to occupy cation vacancies.

The variability of Prussian blue's composition is attributable to its low solubility, which leads to its rapid precipitation without the time to achieve full equilibrium between solid and liquid.

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), an adult male can eat at least 10 g of Prussian blue per day without serious harm.

[48][49] Radiogardase (Prussian blue insoluble capsules [50]) is a commercial product for the removal of caesium-137 from the intestine, so indirectly from the bloodstream by intervening in the enterohepatic circulation of caesium-137,[51] reducing the internal residency time (and exposure) by about two-thirds.

[2] Prussian blue is a common histopathology stain used by pathologists to detect the presence of iron in biopsy specimens, such as in bone marrow samples.

A thin layer of nondrying paste is applied to a reference surface and transfers to the high spots of the workpiece.

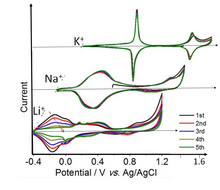

[56] Prussian blue proper (the Fe-Fe solid) shows two well-defined reversible redox transitions in K+ solutions.

The low and high voltage sets of peaks in the cyclic voltammetry correspond to 1 and ⅔ electron per Fe atom, respectively.