Wacker process

[6] At the time, many industrial compounds were produced from acetylene, derived from calcium carbide, an expensive and environmentally unfriendly technology.

[7] In the meanwhile Hoechst AG joined the race and after a patent filing forced Wacker into a partnership called Aldehyd GmbH.

The heterogeneous process ultimately failed due to catalyst inactivation and was replaced by the water-based homogeneous system for which a pilot plant was operational in 1958.

Problems with the aggressive catalyst solution were solved by adopting titanium (newly available for industrial use) as construction material for reactors and pumps.

The reaction mechanism for the industrial Wacker process (olefin oxidation via palladium(II) chloride) has received significant attention for several decades.

A modern formulation is described below: The initial stoichiometric reaction was first reported by Francis Clifford Phillips in his doctoral dissertation on the composition of Pennsylvanian natural gas defended in 1893.

Air, pure oxygen, or a number of other reagents can then oxidise the resultant CuCl-chloride mixture back to CuCl2, allowing the cycle to continue.

[11] Later, stereochemical studies by Stille and coworkers[12][13][14] support an anti-addition pathway, whereby free hydroxide attacks the ethylene ligand.

[15] Kinetic studies were conducted on isotopically substituted allyl alcohols at standard industrial conditions (with low-chloride concentrations) to probe the reaction mechanisms.

Work by Hosokawa and coworkers[21] yielded a crystallized product containing copper chloride, indicating it may have a non-innocent role in olefin oxidation.

Finally, an ab initio study by Comas-Vives, et al. [22] involving no copper co-catalyst found anti-addition was the preferred pathway.

[23] A different kinetic rate law with no proton dependence was found under copper-free conditions, indicating the possibility that even small amounts of copper co-catalysts may have non-innocent roles on this chemistry.

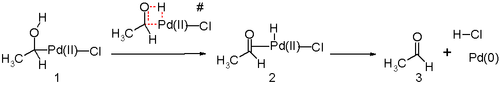

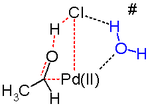

Another key step in the Wacker process is the migration of the hydrogen from oxygen to chloride and formation of the C-O double bond.

Generally, the choice of method is governed by the raw material and energy situations as well as by the availability of oxygen at a reasonable price.

In general, 100 parts of ethene gives: and other minor side products The advent of Wacker Process has spurred on many investigations into the utility and applicability of the reactions to more complex terminal olefins.

Clement and Selwitz[28] were the first to find that using an aqueous DMF as solvent allowed for the oxidation of 1-dodecene to 2-dodecanone, which addressed the insolubility problem of higher order olefins in water.

Two years after, Tsuji[30] applied the Selwitz conditions for selective oxidations of terminal olefins with multiple functional groups, and demonstrated its utility in synthesis of complex substrates.

A water molecule then attacks the olefin regioselectively through an outer sphere mechanism in a Markovnikov fashion, to form the more thermodynamically stable Pd(Cl2)(OH)(-CH2-CHOH-R) complex.

The use of sparteine as a ligand (Figure 2, A)[33] favors nucleopalladation at the terminal carbon to minimize steric interaction between the palladium complex and substrate.