History of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

The Italian Fascists imposed totalitarian rule and crushed the political and intellectual opposition while promoting economic modernization, traditional social values, and a rapprochement with the Roman Catholic Church through the Lateran Treaties which created the Vatican City as a rump sovereign replacement for the Papal States.

For this reason, historians sometimes describe the unification period as continuing past 1871, including activities during the late 19th century and the First World War (1915–1918), and reaching completion only with the Armistice of Villa Giusti on 4 November 1918.

Italy's political arena was sharply divided between broad camps of left and right which created frequent deadlock and attempts to preserve governments, which led to instances such as conservative Prime Minister Marco Minghetti enacting economic reforms to appease the opposition such as the nationalization of railways.

Depretis put through authoritarian measures, such as banning public meetings, placing "dangerous" individuals in internal exile on remote penal islands across Italy, and adopting militarist policies.

This system brought almost no advantages, illiteracy remained the same in 1912 as before the unification era, and backward economic policies, combined with poor sanitary conditions, continued to prevent the country's rural areas from improving.

Peasants without stable income were forced to live off meager food supplies, disease was spreading rapidly, plagues were reported, including a major cholera epidemic which killed at least 55,000 people.

On 29 July 1900, at Monza, King Umberto I was assassinated by the anarchist Gaetano Bresci who claimed he had come directly from America to avenge the victims of the repression, and the offense given by the decoration awarded to General Bava Beccaris.

Critics from the political left called him ministro della malavita ("Minister of the Underworld"), a term coined by the historian Gaetano Salvemini, accusing him of winning elections with the support of criminals.

Italy's recent success in occupying Libya as a result of the Italo-Turkish War had sparked tension with its Triple Alliance allies, Germany and Austria-Hungary, because both countries had been seeking closer relations with the Ottoman Empire.

[72] The protests that ensued became known as "Red Week" as leftists rioted and various acts of civil disobedience occurred in major cities and small towns such as seizing railway stations, cutting telephone wires and burning tax-registers.

For the liberals, the war presented Italy a long-awaited opportunity to use an alliance with the Entente to gain certain Italian-populated and other territories from Austria-Hungary, which had long been part of Italian patriotic aims since unification.

Today, while Italy still wavers before the necessity imposed by history, the name of Garibaldi, resanctified by blood, rises again to warn her that she will not be able to defeat the revolution save by fighting and winning her national war.– Luigi Federzoni, 1915[74]Mussolini used his new newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia and his strong oratorical skills to urge a broad political audience – ranging from right-wing nationalists to patriotic revolutionary leftists – to support Italy's entry into the war to gain back Italian-populated territories from Austria-Hungary, by saying "enough of Libya, and on to Trento and Trieste".

The pact ensured Italy the right to attain all Italian-populated lands it wanted from Austria-Hungary, as well as concessions in the Balkan Peninsula and suitable compensation for any territory gained by the United Kingdom and France from Germany in Africa.

The Italian government was infuriated by the Fourteen Points of Woodrow Wilson, the President of the United States, as advocating national self-determination which meant that Italy would not gain Dalmatia as had been promised in the Treaty of London.

Before World War I, Mussolini had opposed military conscription, protested against Italy's occupation of Libya and was the editor of the Socialist Party's official newspaper, Avanti!, but over time he simply called for revolution without mentioning class struggle.

[123] In 1914, Mussolini's nationalism enabled him to raise funds from Ansaldo (an armaments firm) and other companies to create his newspaper, Il Popolo d'Italia, which at first attempted to convince socialists and revolutionaries to support the war.

This early Fascist movement had a platform more inclined to the left, promising social revolution, proportional representation in elections, women's suffrage (partly realized in 1925) and dividing rural private property held by estates.

Christopher Duggan, using private diaries and letters, and secret police files, argues that Mussolini enjoyed a strong, wide base of popular support among ordinary people across Italy.

[157] Another organization the Opera Nazionale Balilla (ONB) was widely popular and provided young people with access to clubs, dances, sports facilities, radios, concerts, plays, circuses and outdoor hikes at little or no cost.

[207] Adolf Hitler decided that the increased British intervention in the conflict represented a threat to Germany's rear, while German build-up in the Balkans accelerated after Bulgaria joined the Axis on 1 March 1941.

The Independent State of Croatia considered the ceding of the Adriatic Sea islands to be a minimal loss, as in exchange for those cessions, they were allowed to annex all of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, which led to the persecution of the Serb population there.

Under Italian army commander Mario Roatta's watch, the violence against the Slovene civil population in the Province of Ljubljana easily matched that of the Germans[209] with summary executions, hostage-taking and hostage killing, reprisals, internments to Rab and Gonars concentration camps and the burning of houses and whole villages.

On 5 August 1943, Monsignor Joze Srebnic, Bishop of Veglia (Krk island), reported to Pope Pius XII that "witnesses, who took part in the burials, state unequivocally that the number of the dead totals at least 3,500".

[221] Although other European countries such as Norway, the Netherlands, and France also had partisan movements and collaborationist governments with Nazi Germany, armed confrontation between compatriots was most intense in Italy, making the Italian case unique.

But Italy itself proved anything but a soft target: the mountainous terrain gave Axis forces excellent defensive positions, and it also partly negated the Allied advantage in motorized and mechanized units.

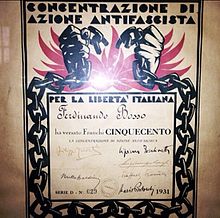

[246] The Italian General Confederation of Labour (CGL) and the PSI refused to officially recognize the anti-fascist militia and maintained a non-violent, legalist strategy, while the Communist Party of Italy (PCd'I) ordered its members to quit the organization.

Many Italian anti-fascists participated in the Spanish Civil War with the hope of setting an example of armed resistance to Franco's dictatorship against Mussolini's regime; hence their motto: "Today in Spain, tomorrow in Italy".

[262] Much like Japan and Germany, the aftermath of World War II left Italy with a destroyed economy, a divided society, and anger against the monarchy for its endorsement of the Fascist regime for the previous twenty years.

Umberto II decided to leave Italy on 13 June to avoid the clashes between monarchists and republicans, already manifested in bloody events in various Italian cities, for fear they could extend throughout the country.

Fears of a possible Communist takeover proved crucial for the first universal suffrage electoral outcome on 18 April 1948, when the Christian Democrats, under the leadership of Alcide De Gasperi, obtained a landslide victory.

Legend:

Italian German annexed by Bulgaria .

The Italian zone was taken over by the Germans in September 1943.