Enzyme

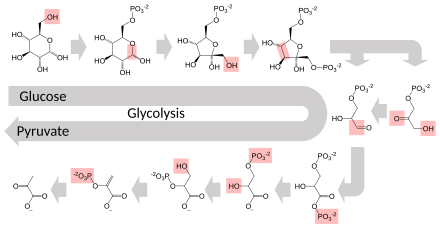

Almost all metabolic processes in the cell need enzyme catalysis in order to occur at rates fast enough to sustain life.

An extreme example is orotidine 5'-phosphate decarboxylase, which allows a reaction that would otherwise take millions of years to occur in milliseconds.

By the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the digestion of meat by stomach secretions[8] and the conversion of starch to sugars by plant extracts and saliva were known but the mechanisms by which these occurred had not been identified.

"[11] In 1877, German physiologist Wilhelm Kühne (1837–1900) first used the term enzyme, which comes from Ancient Greek ἔνζυμον (énzymon) 'leavened, in yeast', to describe this process.

This was first done for lysozyme, an enzyme found in tears, saliva and egg whites that digests the coating of some bacteria; the structure was solved by a group led by David Chilton Phillips and published in 1965.

[20] Enzymes can be classified by two main criteria: either amino acid sequence similarity (and thus evolutionary relationship) or enzymatic activity.

Each enzyme is described by "EC" followed by a sequence of four numbers which represent the hierarchy of enzymatic activity (from very general to very specific).

[27] Enzyme denaturation is normally linked to temperatures above a species' normal level; as a result, enzymes from bacteria living in volcanic environments such as hot springs are prized by industrial users for their ability to function at high temperatures, allowing enzyme-catalysed reactions to be operated at a very high rate.

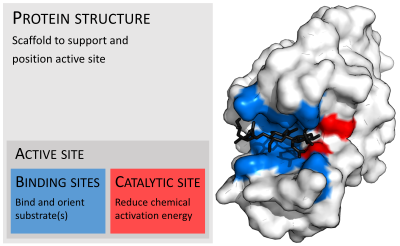

[31] Enzyme structures may also contain allosteric sites where the binding of a small molecule causes a conformational change that increases or decreases activity.

[32] A small number of RNA-based biological catalysts called ribozymes exist, which again can act alone or in complex with proteins.

Many enzymes possess small side activities which arose fortuitously (i.e. neutrally), which may be the starting point for the evolutionary selection of a new function.

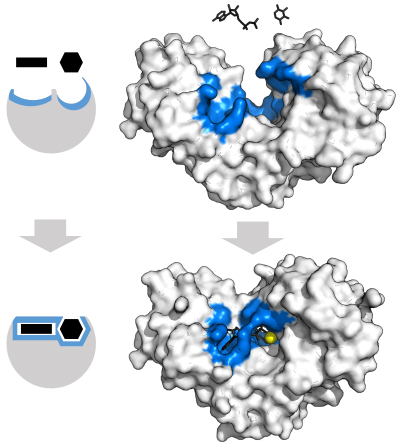

[43] The active site continues to change until the substrate is completely bound, at which point the final shape and charge distribution is determined.

[44] Induced fit may enhance the fidelity of molecular recognition in the presence of competition and noise via the conformational proofreading mechanism.

For example, proteases such as trypsin perform covalent catalysis using a catalytic triad, stabilize charge build-up on the transition states using an oxyanion hole, complete hydrolysis using an oriented water substrate.

These cofactors serve many purposes; for instance, metal ions can help in stabilizing nucleophilic species within the active site.

These coenzymes cannot be synthesized by the body de novo and closely related compounds (vitamins) must be acquired from the diet.

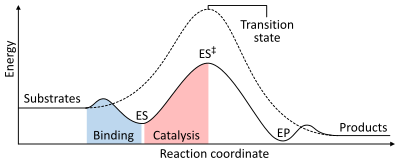

To find the maximum speed of an enzymatic reaction, the substrate concentration is increased until a constant rate of product formation is seen.

Saturation happens because, as substrate concentration increases, more and more of the free enzyme is converted into the substrate-bound ES complex.

Example of such enzymes are triose-phosphate isomerase, carbonic anhydrase, acetylcholinesterase, catalase, fumarase, β-lactamase, and superoxide dismutase.

[70] Michaelis–Menten kinetics relies on the law of mass action, which is derived from the assumptions of free diffusion and thermodynamically driven random collision.

[82] A common example of an irreversible inhibitor that is used as a drug is aspirin, which inhibits the COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes that produce the inflammation messenger prostaglandin.

[83] As enzymes are made up of proteins, their actions are sensitive to change in many physio chemical factors such as pH, temperature, substrate concentration, etc.

Enzymes such as amylases and proteases break down large molecules (starch or proteins, respectively) into smaller ones, so they can be absorbed by the intestines.

In ruminants, which have herbivorous diets, microorganisms in the gut produce another enzyme, cellulase, to break down the cellulose cell walls of plant fiber.

Most central metabolic pathways are regulated at a few key steps, typically through enzymes whose activity involves the hydrolysis of ATP.

[91]: 141–48 Negative feedback mechanism can effectively adjust the rate of synthesis of intermediate metabolites according to the demands of the cells.

This helps with effective allocations of materials and energy economy, and it prevents the excess manufacture of end products.

Like other homeostatic devices, the control of enzymatic action helps to maintain a stable internal environment in living organisms.

Enzymes in general are limited in the number of reactions they have evolved to catalyze and also by their lack of stability in organic solvents and at high temperatures.

As a consequence, protein engineering is an active area of research and involves attempts to create new enzymes with novel properties, either through rational design or in vitro evolution.